The Bead-and-comb loom

THE BEGINNINGS

A few years ago, I began a personal design project.

This project involved the textile structures that today are often called ‘sprang’ (I prefer weft-less weaving). Usually, these structures are made by hand, either on a frame or as a needlework technique. In either technique, the component twists, plies, or plaits are inserted manually.

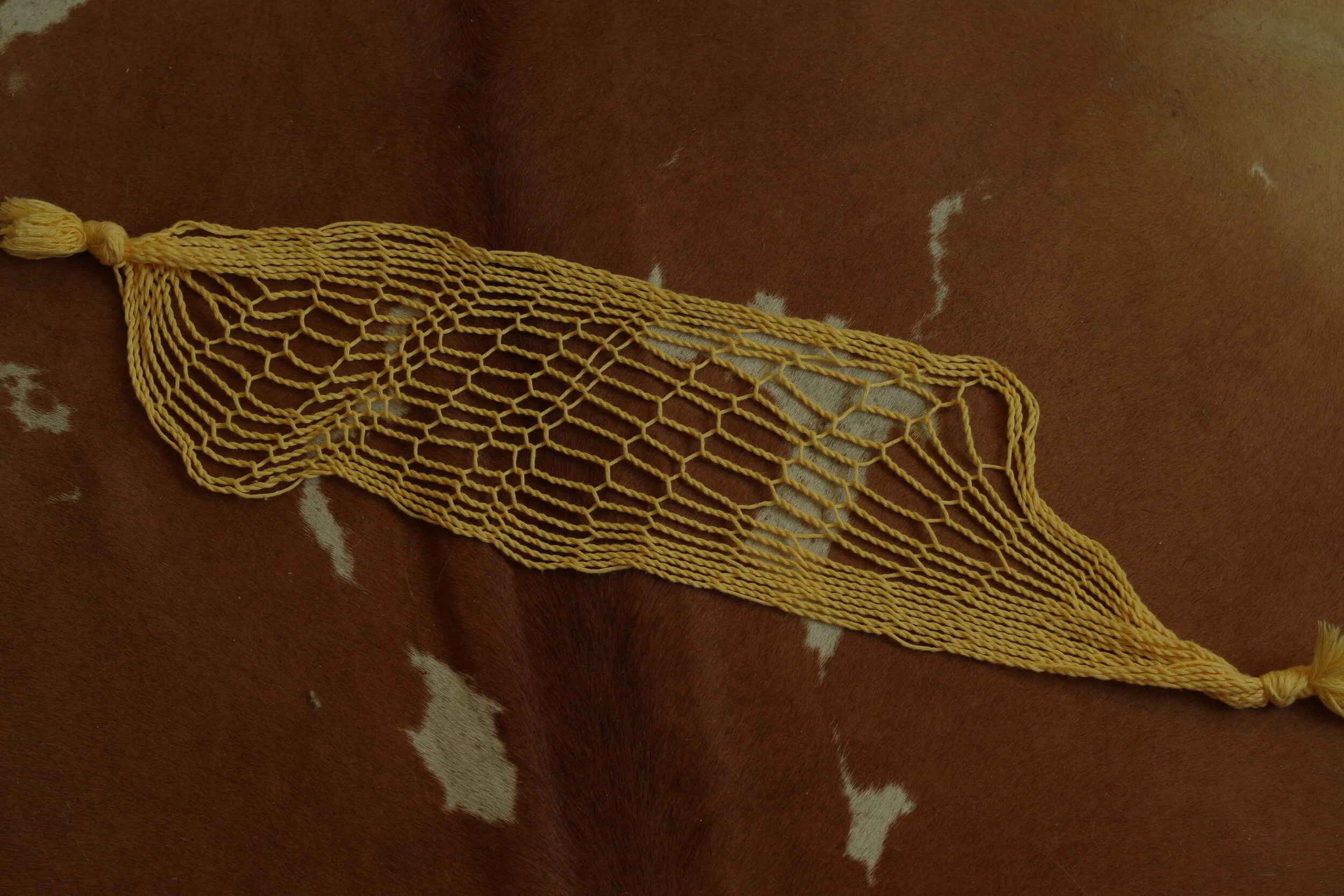

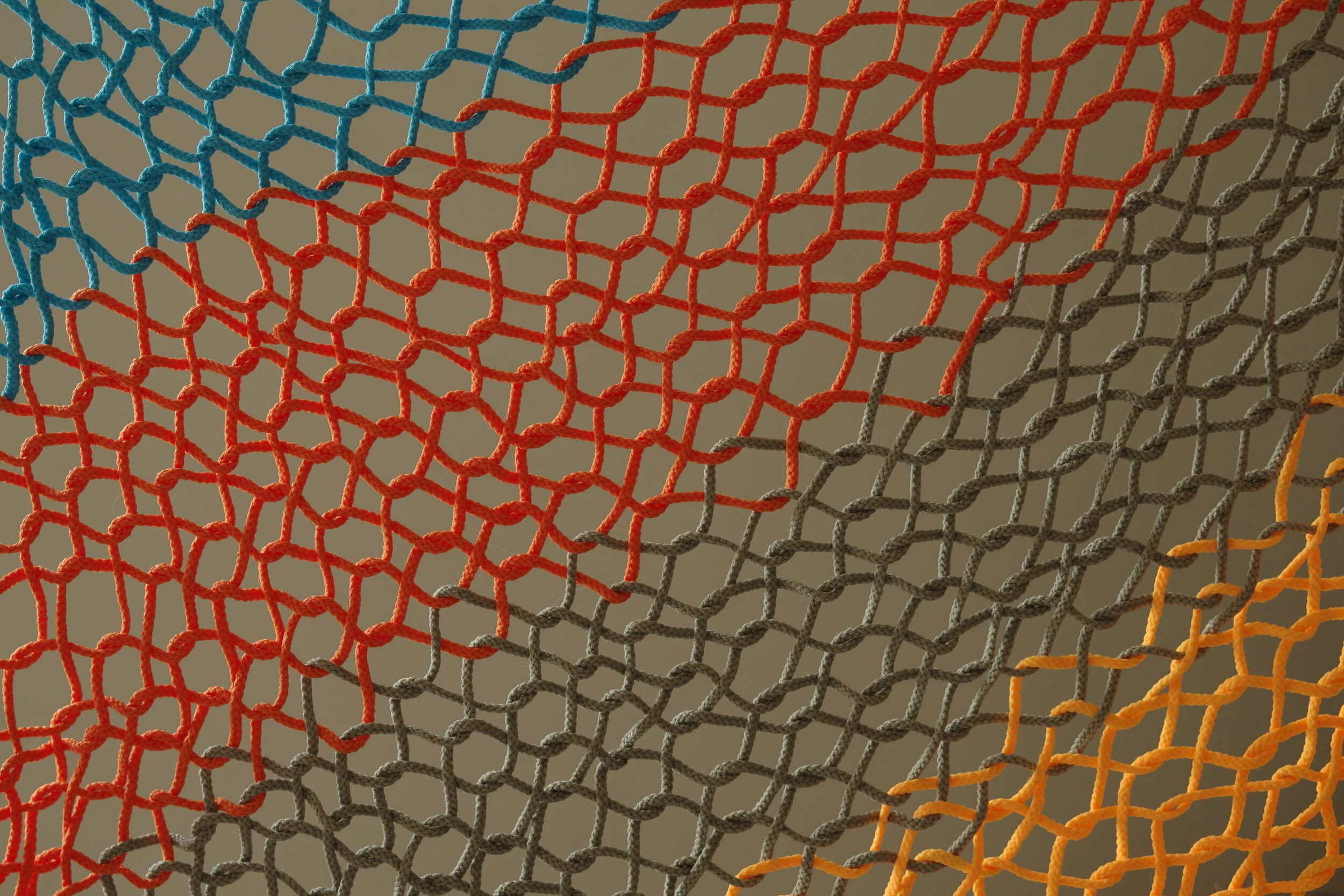

Nowadays, hammocks, chain-link fencing, and, arguably, shoelace closures are all modern, extant, even ubiquitous examples of this type of structural approach. These aside, weft-less fabrics have played a somewhat minor role in the textile industry, and have persisted largely as historical re-creation, or niche design, art, and craft.

An abstracted view of the structure of weft-less weaving.

Chain-link fencing, demonstrating the inherent dynamism and flexibility of interlinking.

Shoelace closures, demonstrating both interlinking and interlacing.

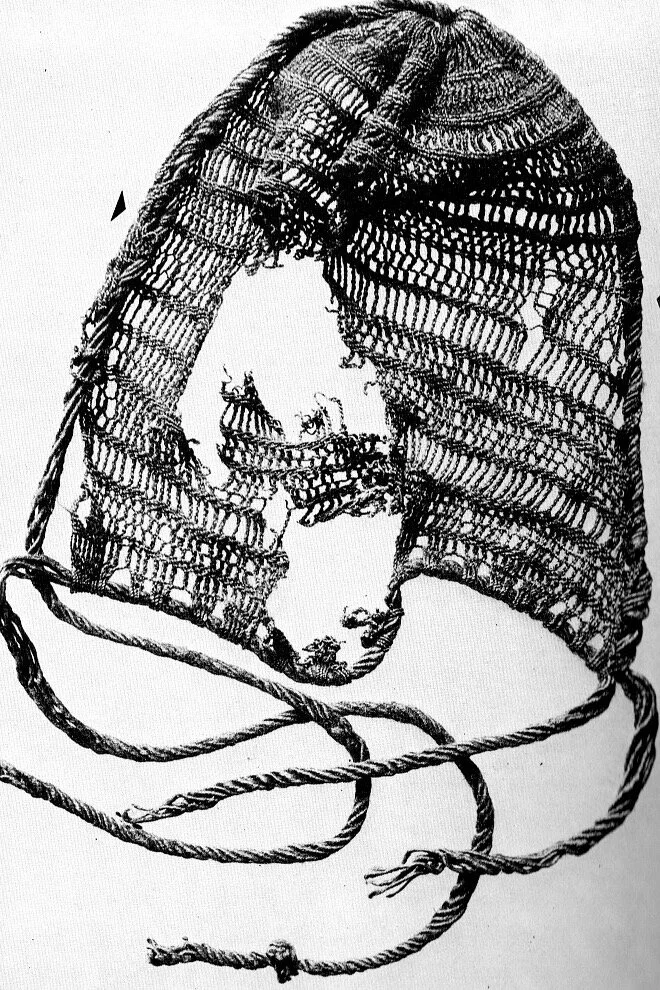

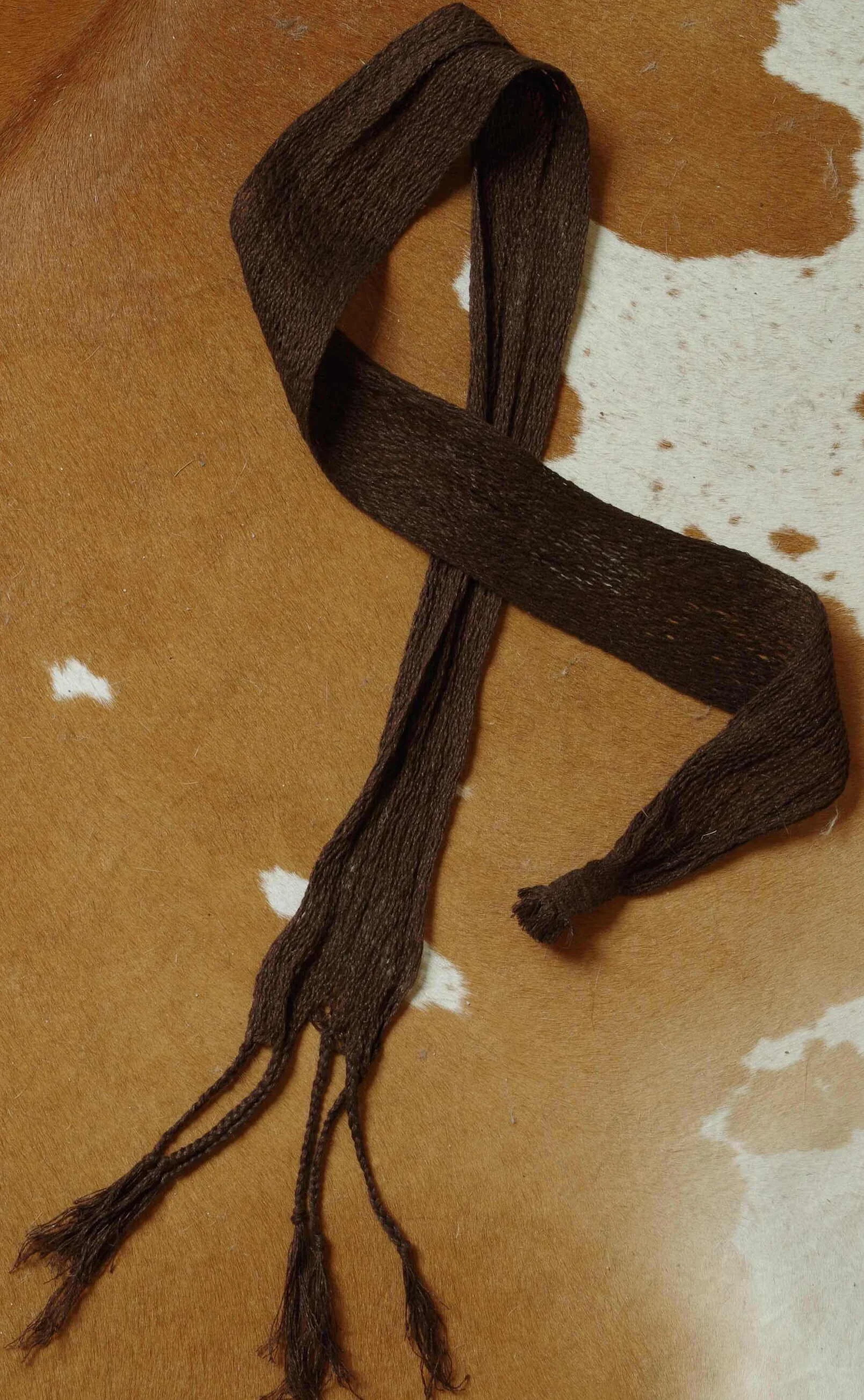

However, these technologies - the textiles themselves - represent a family of ancient structures possibly pre-dating and definitively coexisting with knitting and weaving, felt, etc for thousands of years. Notable surviving examples include the hairnet of the woman found at Borum Eshoj, dating to 1400 BCE; and, the Braddock Sash, received by then-Virginia Colonel George Washington as a battlefield promotion by his mortally wounded commander, Major General Edward Braddock, at the ill-fated Battle of the Monongahela in 1755.

The hammock, illustrated here as a pre-columbian american folkway. Engraving by Theodor Galle after Stradanus, circa 1630. Public domain via Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hammock

Current historical evidence indicates that civilizations from the ancient Peruvians to the ancient Egyptians to northern Europeans found a great variety of function, utility, and beauty in products in seemingly all manner of fiber and preparation from cotton and linen to wool and hair. Products of antiquity include head wraps and hairnets, bags, belts and sashes, tunics, leggings and socks, and so on.

The hairnet of the woman from Borum Eshoj. Danish Bronze Age, circa 1400 BCE. Reproduced from Collingwood, Peter. The Techniques of Sprang (1974).

Camelid Hair Mantle (circa 200-100 BCE), Ocucaje, Peru. Public Domain via The Met. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/315048

Middle Kingdom Egyptian Estate Figure, circa 1975 BCE. Public Domain, The Met via Wikimedia Commons https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Clothing_in_ancient_Egypt

Washington in the Uniform of a British Colonial Colonel. Charles Willson Peale, 1772. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Washington_1772.jpg

Traditional methods of achieving these structures include frame sprang, which involves stretching warp yarns across a frame of variable length, and then manipulating the yarns in sequence to incorporate a mirrored twist which is then worked back to the frame stretcher beams. Another method is to stretch the work across posts (or a rigid frame) and then use a narrow shuttle or bobbin to - again - manually insert twist into the structure.

Making shaped head-dresses, Moravia, 1954. Reproduced from Collingwood, Peter. The Techniques of Sprang (1974).

Fabricating a traditional Mayan hammock, using a small shuttle or bobbin to manually insinuate twist. Photo attributed to Abraham Razu. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hammock

It is my opinion that weaving without weft is one of the great textile idioms of humanity, and yet under-represented in today’s global civilization! My sense is that this is largely due to the fact that traditional processes have resisted mechanization… and lacking machine efficiency, it is simply too costly for these materials to be considered as mainstream in modern markets. (I should emphasize that I consider my work a sort of technological art project - I am primarily concerned with material culture and human expression in the midst of economic realism).

THE BEAD-AND-COMB LOOM

Initially, I became interested in interlinking via an exploration of machine knitting tensioning (I still consider myself a knitter at heart!). One evening, as I wrapped yarn around a dowel to conceptually model ‘pre-looping’ of weft knitting, I had an ‘Aha!’ moment in re-imagining the resulting helix as a warp element. Intrigued at the idea of how several of these helices might interact, I laid out a few yarns in a sensible pattern on the floor. The result was enough for me to research and, sure enough, discovered that this mode of textile was apparently called ‘sprang’.

While exploring the history and traditions of interlinked fabric processes, the premise of my project began to take shape: My goal was to develop a device that interlinks warp yarns, row-by-row, without the operator handling the yarn directly; the broad strategy being to achieve a folk technology that could be scaled for industrial use. Indeed, throughout the design process, my greatest efforts have been in whittling down the mechanism to an elemental, essential design - as simple and open as possible - so that further developments may emerge responsively.

My solution is complete. I call it the Bead-and-Comb Loom.

This device is inexpensive and requires only a few commonly found elements. It is simple to build. Once seen and briefly demonstrated, preparing and operating this loom should prove user-friendly, even intuitive. It can be arranged in several ways depending on space constraints, project requirements, and user preference. It is portable. It is, in my humble opinion, a design worthy of publication and I am very pleased to present it.